The Institutional Design of Democracy

Dragoș COSMESCU

Independent Researcher

Abstract: In this paper, I argue that institution building is essential for the success of the democratic transition and consolidation. Upon setting out to establish a democratic regime, there are various constitutional designs available. Although all appear equally suitable for building a stable democracy, I demonstrate that particular traits of certain political systems can allow political actors to weaken the quality of democracy in that state, if not do away with it all together. As such, I have observed the main differences between presidential, parliamentary and mixed systems, and I have also examined the impact of various electoral rules on the configuration of the political arena. The conclusion shows that parliamentary regimes with proportional electoral systems have the strongest democratic features.

Keywords: democracy, presidentialism, elections, transition.

The institutional design of a regime is essential to the degree to which it is able to satisfy its political body, which will allow the regime to survive, hence stabilise and then consolidate. If institutions are created coherently and harmoniously, they will work effectively together, which will provide – at least in terms of governance and administrative bureaucracy – positive results that are felt and appreciated as such by the populace.

In the case of the democratic regime as well, the institutional design is essential for the stability of the regime and its strengthening. The institutional structure provides the framework within which the political actors rise to power and the means available to them in order to govern effectively (from the economic, social, administrative, etc. viewpoint). The effectiveness of governance arrangements directly affects the level of satisfaction of the citizens (who form the political base of support and recruitment). Their satisfaction is essential to the perpetuation of the regime. Larry Diamond summarises the causal link: “democracy requires popular support. Support comes from legitimacy. Legitimacy requires [executive policy] performance”[1] .

The democracy’s constitutional design is also the one that enables citizens to express their opinions concerning the performance of the regime and to express their satisfaction by supporting the regime. For democracy, the regime support manifests itself through the citizens’ participation in the democratic game, through elections. These can bring to power another executive, but, obviously, this does not change the nature of the regime.

The strengthening of democracy depends on political and economic factors – both depending on the institutional design – which generate satisfaction amongst political actors. Thus, a good design of democratic government maximises these results, while, in the opposite case, the democratic regime may be perceived as inefficient, even corrupt.

In contemporary democracies, the rule of law requires institutionalised and coherently articulated organisations. The choice of the state’s political institutions is essential. These will create incentives for the political actors, and the political actors will define identities and determine how the decision making works in a system. The design of political institutions is very important during the transition to democracy. (Obviously, in the consolidation phase of the democratisation process, they already exist and function properly, otherwise it would not be a successful transition to democracy). In the transition phase, these are just being built, and their design is largely at the discretion of political actors. They are interested in building them in such a way as to maximise their potential political gain.

The type of institution building must be close to the plurality of political options available in a democracy, it is important to allow every voice to be heard.[2] At the center is a set of rights and liberties, because it would be impossible to build institutions, by the political elite, with the lack of support provided by the citizens. The Parliament is the place for debate and enactment of laws, while the judicial system is where conflicts of interests are discussed and decided. Together, the parliament and judicial institutions are perceived as organizations providing the social efficiency of the laws.

The democratic regime must also meet the expectations of organised political actors. Since they strive to gain access to political power, their expectations are related to the possibility of taking the power. Democracy provides the opportunity for all political actors, at regular intervals, regardless of the results of the previous government to rise to power. Since elections are free and regular, all political forces have the legal opportunity to reach the highest levels of power, hence their interest in supporting democratic regimes to the utmost of their capacities. Since democracy is the regime which ensures the chance to come to power at regular (and relatively short) intervals, the political actors have a much higher cost for the total seizure of power and perversion of the democratic system, than to accept it.

Institutions stimulate the support for the regime by the political class, through the possibility of reaching the government by peaceful means and participating in the redistribution of resources, and, in turn, the performance of the political elite while in power will draw public support for the democratic institutions implemented during the transition. The legitimacy of a democratic regime is embodied by the democratically elected representatives of the political body (the citizens).

In a democracy, the political system structure addresses directly the citizens, since political parties are made up of groups of individuals with common political goals. The political class is representative of the citizens of those parties, and so the political body is reflected indirectly in the government.

Once in power, the politicians must provide citizens with effective leadership, responsive to their needs and demands. These may be demands expressed by the governing party supporters and promises made in the victorious electoral campaign, or the expressed or perceived needs of a wider part of the political body of that state. In any case, whether meeting prior or anticipating existing demands, considering the future electoral performance, the political elite must demonstrate that it is able to govern efficiently. The principles of democracy are found in the institutional construction, so government efficiency depends largely upon the quality of state institutions. In this way, citizens are able to sanction not only the parties in government, but also the entire institutional system. An effective democratic governance, based on functional and effective institutions, attracts public support, which in turn substantiates the stability of the regime. Similarly, government failure can easily be blamed on new institutions and mechanisms implemented in the transition to democracy, resulting in a citizen lack of trust and regime instability.

Institutional structure defines the rules of government and the path to power – very important conditions for the political class. The latter, organised in political parties, is interested in the opportunities to participate in government and in the regulations concerning the management of state resources. This is ensured by a broad inclusion in the political body, and the broader political inclusion – as far as possible all political forces, although there are cases of anti-system groups excluded – is guaranteed by the democratic regime. Democracy’s institution building does not guarantee the presence in power of all political forces, but the possibility of reaching the power; to the same extent that the institutional structure of other forms of government limits the access to power to a small group of political forces and limits the scope of the political body.

Consequently, we will see the major characteristics of democratic institution building. We will see what structural design offers more satisfaction on the political market and what features make certain democratic subtypes more suitable for democratic consolidation, while others have inherent conflicts that make them unstable and prone to fall into formal democracy and authoritarianism.

There are three types of constitutional design, corresponding to three subtypes of democratic regimes: parliamentarism, presidentialism and semi-presidentialism (a combination of the first two). Any contemporary democracy is either parliamentary (almost all European democracies) or presidential (U.S., Latin America, Africa) or mixed (France, Romania).

Arend Lijphart has a different approach in his Models of Democracy (1999), where he identifies two subtypes of democracy: the majoritarian one and the consensual one. Although the source of this conceptualization is undoubtedly the electoral system used to elect the supreme executive function (plurality, proportional), his subtypes describe a political culture based either on the winner-takes-all principle, or on the negotiations needed to reach a decision acceptable to all stakeholders (consensus).

Even within the same subtype of democratic system there are differences of nuance[3] . For example, both the U.S. and Mexico are presidential regimes, but the American Congress is more powerful than the Mexican one. Also, Russia and Romania are both called semi-presidential regimes, but in Russia the Parliament has a very small role, after the constitutional changes forced by Boris Yeltsin, while in Romania it is important for the government of the Prime Minister to maintain its power, and this is important even for the President.

In the parliamentary system, the executive is composed of ministers voted by the parliament, led by a prime minister appointed on the basis of negotiations between political parties, represented in parliament after a direct election. The government depends on the support of the parliament.

Parliamentary systems are those in which the head of state and the Prime Minister are two different functions. The head of state in these systems has a largely ceremonial function, for the real power belongs to the chief of the executive. The latter is not directly elected by the citizens, but by the legislature (based in its turn on direct popular vote). There are also constitutional monarchies, where the head of state is succeeded mostly on natural causes. To be invested and maintain in power, a prime minister needs the support of the parliamentary majority.

In a presidential system, the executive power is held by the President, who appoints a cabinet responsible only before him. Presidents cannot propose legislation, but has the right to veto it. The head of state is elected directly by the voters (most presidential democracies), or indirectly, by MPs (South Africa, Moldova).

The presidential system is centred on the figure of the President, elected directly by the voters and effectively independent of the legislature. In a presidential system, the head of the executive is elected by direct popular vote (the U.S. is an exception, but on the other hand, the Electoral College has little independence as to the vote of the federal states). Executive power is not influenced by the results of elections and is not determined by post-election negotiations, as in parliamentary democracies. In presidential systems, the president is the head of the executive.

In mixed, semi-presidential systems, the executive is double, with a president elected directly by the electorate and a prime minister (and his cabinet) voted by the legislature and resulted from negotiations between parliamentary parties. The President is head of state and but not head of the executive. Semi-presidential systems are found in France, Finland and Romania.

The semi-presidential system appeared in the Weimar Republic (1919), in order to avoid the dangers of personalisation of the presidential power. It was considered that the presence of a strong parliament in the institutional construction will restrain the concentration of power.

The mixed regime is complicated and unnecessary. The existence of two centres of power only hinders the work of the government and creates unnecessary tensions. Since the president is elected by the citizens, he runs the campaign with a governing program. But obviously there is no way to implement such an election platform, because the president lacks both the legal means and the executive and administrative powers. The only one able to implement an economic, social and political program is the government with its prime minister, because they are endowed with the respective powers. Since the President does not control the ministries and their subordinate administrative units, he cannot decide on any such issues. Thus, in reality, his electoral program can be put into practice only if the government wants to. In order for the presidential institution to be effective and to justify its position, there should actually be a government ally of the President, to implement his political proposals (though not constitutionally required to do so). Otherwise, the system’s dualism merely complicates the work of the executive and reveals the inefficiency, and even futility, of the two power centres simultaneously. The president either has a friendly government – which implements his policies – or has a hostile government, which effectively prevents all his initiatives to come true. In both cases, it is revealed that the real centre of power in the mixed system is still the Prime Minister, without which the president is powerless or obstructive at most. What emerges is actually the futility of presidential powers, as well as the inefficiency of mixed system.

In terms of presidential office’s position as impartial mediator, it should be required that the president be not the leader of the party who nominated him, because he would always remain tied to the partisan structure he controlled. A more real impartiality would be obtained if the candidate were a secondary party politician, like the presidents in parliamentary republics.

This again reveals the importance of building harmonious institutions. Institutional design is very important for the success of the transition and the subsequent consolidation of the democratic regime. Even in a country which started the transition under ambiguous auspices, effective institution building – a strong parliament despite a semi-presidential regime – has stimulated democracy: “Favourable institutional choices have facilitated the democratisation of Mongolia. Of particular importance are the shape regime included in the new constitution and electoral rules that organise access to public office”.[4]

The most common democratic systems are the parliamentary and presidential ones; subsequently, the main problem in institution building in transition to democracy is the choice between parliamentary assembly or presidential seat. As we shall see, this choice is crucial to the chances of success of the transition and of the democratic consolidation.

The choice between these types of government is essential to the success of democratic transition and the strengthening of democracy. We shall present now the differences between parliamentary and presidential power.

Presidentialism presents inherited institutional flaws, such as executive-legislative deadlock, fixed term (impossible to curtail ahead of schedule) and, especially, exhibits the authoritarian tendencies of the personalisation of the presidential office.

A fundamental difference between presidentialism and parliamentarism is the relationship between the head of state and the representative assembly. The first is a system of mutual independence between the executive and the legislature, and the second is one of mutual dependence.

The parliamentary system is one of mutual dependency: the executive must be supported by a parliamentary majority, otherwise it risks falling to a non-confidence vote. On the other hand, a presidential system is a system of mutual independence: the executive is headed by the President, regardless of the composition of the parliament, which cannot alter the policies of the President (he was elected for a fixed period, independently of the parliament). Since in a parliamentary regime governments risk losing legislative support, they pay more attention to the content of their legislative proposals. In a presidential system one cannot solve the conflict between the majority and the president, because of the independence of the two institutions and their relatively equal power: “there is no democratic principle to determine which of the President or Parliament truly represents the will of the people”.[5]

Institutional conflicts – so common in presidential and semi-presidential systems – are avoided in parliamentary systems, because the government is not independent of the legislature. Thus, if the parliamentary majority wants a policy change, it can replace the government through a vote of non-confidence, without creating a political crisis.

The data show that a strong legislative is undoubtedly a good thing for democracy and democratisation. This power of the Parliament was best measured by Steven Fish and Matthew Kroenig, who measured the power of national legislatures through the Index of Parliamentary Powers (PPI). It is based on 32 elements that cover the parliament’s ability to monitor the bureaucracy and the president, freedom from presidential control, the parliament’s authority in specific areas and resources available for its work, etc. Their study shows that the relationship between the parliament and democracy is strong and positive.

Presidential political systems are designed so that the parliament might not hinder the work of the executive, except in rare situations (very large majorities). Obviously, the electoral system used for the direct election of the president is plurality, not proportionality. We confront here with the practical situation in which a politician, even if elected by a small margin, decides and executes the policies of a state, without significant opposition. The quality of such a democratic constitutional design is limited.

Studies show[6] that the separation of the presidential from the general election, as well as the fixed and rigid term of office of the president, generate inter-institutional conflicts that make it difficult, if not impossible, to solve political crises.

This hypothesis of the difficult combination between presidentialism and certain institutions, or rather the different configurations of institutions (mainly a minority parliament) is complemented by other variables, such as limiting the number of presidential mandates, and, especially, the degree of concentration of the decision-making process in the hands of a single person, and converge to explain the poor performance and the fragility of democratic presidential regimes: “The executive power is formed by post-election agreement between the parties [...] while a president can serve their mandate with as little parliamentary support”. [7]

Mainwaring and Shugart show that presidentialism is “particularly problematic when the multiparty system is highly fragmented, and parliamentary elections are held more frequently than presidential ones”. [8] They believe that the most fragile institutional combination is that of presidentialism and multipartism (because multi-party system would increase the likelihood of a minority government). A very elaborate study prepared by Cheibub, Przeworski and Saiegh[9], and conducted on democracies existing between 1946 and 1999, shows that coalition governments were formed in 50% of the cases where the presidential party has the majority in congress. Also, minority governments are as effective as majority governments, in both democratic systems (presidential and parliamentary). Moreover, the stability of the coalition government had no impact on the survival of democracy in both types of democratic government.

However, Mainwaring and Shugart were mistaken when they recommended single round presidential election[10] , instead of choosing the two-turns system, because, in this case, although candidates are discouraged from electoral arrangements between rounds, there is a risk that victory goes to a candidate who meets a minority of the voters’ support. Although Allende’s case is not one that fits the situation of direct election (being ultimately elected by a vote in parliament), the reality is that its actual support, of only 33% of the population, has created serious problems of legitimacy, while the lack of cohabitation with political forces representing the remaining two-thirds of the society radicalised their united opposition. In a parliamentary system, Allende would have simply been replaced by the representatives’ vote.

Presidentialism makes it hard to cope, democratically, with a political crisis. Some presidents have stepped down in the face of acute crises (Argentina, 2001), but the resignation is a personal act of a president, that is a non-institutional way of solving the crisis. Very rigid presidential terms make almost impossible to replace an incompetent or unpopular head of state (situation easily solved in a parliamentary system, by the loss of confidence and support of the legislature).

This deadlock is sometimes solved only through a coup (either against the president, or an autogolpe by the president). Moreover, the defining nature of this deadlock - which excludes constitutional and institutional means of replacing the president – makes a coup to appear as the only viable way of replacement, which, however, destabilises the democratic system and is most likely to replace it (Chile, 1973). Here lies the fragility of presidentialism and explains the short duration of existence of presidential democracies: “The danger of the presidential election - zero sum game - is amplified by the rigidity of fixed term presidential term. Winners and losers are defined in the most emphatic manner for the duration of the presidential term. Losers have to wait at least four or five years without access to executive power.”[11]

In a presidential system, the government cannot be replaced, even if the majority wants it. The deadlock arises precisely from the power of the president and its privileged position in relation to parliament. In the parliamentary system, a coalition can be formed by a minority party, if it provides sufficient ministerial portfolios to convince other political forces to join it, otherwise you can return to running elections and the coalition-making process is repeated.

In a parliamentary system, the government must have the support of a parliamentary majority, so the legislature can dismiss the government, if it chooses so. The prime minister may be changed at any time, with or without elections. Jose Antonio Cheibub shows that 163 of the 291 prime ministers of countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), in the period from 1946 to 1995, left their office in between general elections[12] . In a presidential system, however, the executive can change very rarely between elections, regardless of its political performance.

There is a rich literature in this field (Linz, Shugart, Mainwaring, Cheibub), which examines the fragility of the presidential regime faced with the authoritarian tendencies of the president and which, in turn, demonstrates the parliamentary regime’s insulation from such real risks.

In his well-known “The Perils of Presidentialism” (1990), Juan Linz argues eloquently in favour of parliamentary democracy, showing that the presidential system has two major flaws: they have rigid and inflexible terms, because of the constitutional powers of their office, and promote a winner-takes-all mentality, that excludes other groups from power sharing, and might even exclude them from political dialogue, negotiation and compromise. Linz demonstrates that in presidential systems institutional weaknesses make them less conducive to the maintenance of democracy than parliamentary systems. He finds that in 1993, only four of the 31 stable democracies - defined in this case as having a life of more than 25 consecutive years - had presidential systems: USA, Venezuela, Costa Rica and Colombia. The only presidential democracies that have experienced a long period of stability were constitutional USA, and Chile that experienced a consolidated democratic regime from 1930 to 1973.

Shugart and Carey’s approach in Presidents and Assemblies (1992) is different. They try to prove that presidential systems are not more vulnerable to nondemocratic threats than parliamentary democracies, even proposing the solution of the mixed republics, to eliminate the extensive presidential powers from the presidential republics. However, this does not mean that they praise the merits of a semipresidential system per se, but only suggest that it would be more desirable than a pure presidential system, precisely because it has a stronger parliament.

These theories reveal causal links starting from the separation of powers characteristic in these systems, and observe that presidentialism is irreconcilably prone to conflict and conclude that such conflicts do undermine democratic institutions.

The life expectancy of democracy in a presidential system is less than 24 years, while it is of 74 years in a parliamentary system[13] . Most contemporary consolidated democracies are parliamentary regimes, where the executive power is generated by legislative majorities and depends on such majorities for its survival in office.

The probability of a democracy to fail in any given year is of 0.0135% in parliamentary systems, and of 0.0419% in the case of presidential republics.[14] The risk of losing democracy is four times higher in a state with a strong presidential office. Regime survival is endogenous with respect to the qualities of different institutional systems.

Presidentialism offers a government that depends on the president whose claims of legitimacy come from the vote of the entire population (although he’s usually elected with results very close to the equilibrium threshold) and who does not need to exercise the fundamental practice of democracy: the dialogue. The interaction amongst powers, inevitable in parliamentary systems, is a much better formula than winner-takes-all to promote efficient and stable democratic regimes.

The most important quality of the presidential executive office is the one that also contains the basis of personal authoritarian government: election by majority vote, directly by the citizens. Relying on popular legitimacy, the person who becomes president may however easily move away from the principles of democratic governance.

In the presidential system, democracy is constantly threatened by authoritarian tendencies, being saved, in reality, only by the preferences of the office holder. For instance, based on the same constitutional provisions, but with totally different interpretations, Giscard d’Estaing was a very democratic head of state, compared to his predecessor as president, General de Gaulle.

Presidential systems often produce presidents who feel they have received a personal mandate which urges them into adopting a policy speech style imbued of the “popular interest” that marginalises organised groups in political life and civil society.

William Riker shows that too much importance is given to the popular vote (and its size), entrusting it with a moral value, a direct legitimacy from the people, a manifestation of popular love, rather than perceiving it as a mere decision on the competence and socio-political programs: “The difference between liberal and populist views is that the populist interpretation of the vote, the views of the majority must be correct and must be respected, because the popular will represents the popular freedom. The liberal interpretation there is no such magical identification. The election result is just a decision and does not require a special moral characteristic.”[15]

Elections are just a way of determining and controlling officials in public positions, and do not assign any supplementary legitimacy on the political actors that occupy that specific position. The legitimation is only that of the office – as part of legitimate institutions working in a legitimate regime – an d not of its temporary holder. A politician is not legitimised by the people, but by the system in which he acts, because he is supported (through the suffrage), and because he operates within a legitimate regime, and not the other way around.

The belief that the popular majority will always find the objective truth is very dangerous and misleading. Accepting the decision of the electorate on any particular issue is absolutely normal in a democracy, and it is not accompanied by additional legitimacy for the simple fact that elections are just a way to decide who will occupy certain high administrative and state offices. The simple respect of the democratic game has not and cannot have additional qualitative aesthetic judgments.

Democratic legitimacy does not arise from the number of votes obtained by a particular political actor, but from complying with the democratic characteristics of the process of succession in office and its functioning. The fact that a citizen holds a political post in accordance with specific constitutional regulations for that office (election, appointment) is legitimizing in itself.

It’s not the amount of votes that grants an increased right in holding an office, but the political practices used in that position. For an office occupied through majority vote, for instance head of state, a citizen is just as legitimate being elected by 70% of the voters, as is the one chosen by 50.1%. Moreover, it is only natural that it takes much more votes to elect a president than a parliamentary, but this does not mean that the legitimacy of the president is different from that of a MP. Not to mention that there are situations where even controversial characters can win the elections in a constituency where the majority does not sanction such shortcomings. Democracy is not a popularity contest. On the contrary, such tendencies hide an authoritative personality: the replacement of the political representation of values and ideas (centre of liberal democracy) with the media representation of a false image.

Precisely because many presidents always emphasise that they are elected directly by the population, in a majority nationwide constituency, it diminishes rather than strengthens legitimacy. Although he may consider himself representative of the entire nation, he could only represent his own voters, which might form just over half of the voters’ turnout (which also is a percentage of those eligible to vote). On the other hand, a prime minister dependent on the parliament will always be the leader of a coalition which – in order to stay in power – should contain representatives of more than 50% of the voters. There are indeed cases of minority governments, but these are unstable and thus short lived, and are also tolerated or even supported by the larger opposition. In the event that they form another parliamentary majority, this can quickly take over the administration of the country, without being hindered by the rigidity and lack of compromise of a presidential term.

Among the 21 states that have experienced democracy for the entire post-war period, 17 are parliamentary regimes, three are mixed and only the U.S. is a presidential regime[16] . Alfred Stepan and Cindy Skach show[17] that many different data sources point to a stronger correlation between democratic consolidation and pure parliamentarism than between strengthening democracy and pure presidentialism. Undoubtedly, parliamentarism is synonymous with contemporary democracy.

The form of government influences the survival prospects of the democratic regime. The political scientists’ opinion on the new democracies of the late 20th century seems unanimous: to survive, they should have parliamentary institutions.[18] Parliamentary systems are built on an approach that requires cooperation and compromise.

The survival of a democratic regime relies substantively on dialogue, negotiation and compromise (the democratic principles) and, procedurally, on the actual chances for any organised political actor to rise to power. These qualities may be missing in presidential systems. Studies, such as that of Cheibub,[19] show that parliamentary democracies have a greater capacity than presidential ones to survive a very varied set of conditions: between 1946-1999, one out of 23 presidential regimes failed (turning into a dictatorship), while only one in 58 parliamentary regimes underwent a regime change.

Parliamentary regimes provide the opportunity that even the smallest political representatives in the legislative assembly be included in a coalition government, making it possible to share power even with very small political forces. This very possible perspective reinforces the trust of all political actors in the democratic system and, consequently, their support for it.

Dialogue is the basis of democracy, because it enables negotiation, tolerance and compromise. The lack of need for political dialogue – like in the case of presidential regimes – may take undemocratic traits. The virtually unassailable position of the presidential administration makes such a head of state far less prone to something else than the imposition of his own views on almost every topic. Confrontation is always less costly than negotiation in a regime with a strong president, especially because negotiation is simply not necessary (the president holds discretionarily the executive power in his hands).

The presidential system is built around a zero sum game, in which the winner takes all and the losers have no significant political voice until the next elections. By a sharp contrast, parliamentary systems provide a positive-sum political game in which each political actor’s interest is to participate in government by agreements with others (negotiation, compromise), and not by exclusion and denial of dialogue (as in the case of a president with executive powers).

Democracy equals parliamentary system. Democracy means dialogue between different political opinions expressed by free and equal citizens. Democracy does not mean a strong personalised government (like the presidential system). The lack of personalisation of the democratic leadership renders charisma useless, while the victors are selected on the basis of policy choices they promise to implement for the benefit of the constituency they represent.

Since the democratic will of the citizens is expressed through elections, the electoral systems are very important in democratic institution building. In a democracy, elections are paramount. Their result is recognised by both winners and losers, and their effects come into force under the form of a functional administration nationwide. “The elections are crucial for the democratisation process and the dismantling of the former regime. They are even more important for the installation, legitimisation and empowerment of the new democratic regime.” [20]

Regarding the elections as an indicator of democracy, Huntington emphasises that democracy is truly instituted in a country in transition when its political system goes through the “test of double alternation in power”.[21]

In a democracy, all major policymaking positions are allocated through regular, free and fair elections. This requires government to be ousted if the majority of voters prefer another governing coalition. Also, all political actors (parties, candidates) should be able to mount an effective campaign, which includes freedom of speech, movement and association.

The elections are institutionalised through electoral laws that determine the electoral systems, which in turn directly influence party systems.

Electoral laws govern the electoral process, from the viewpoint of the conditions under which elections are triggered, the nomination of candidates, the organisation and conduct of the campaign, the vote count and the distribution of seats in the legislature. Such laws may stipulate who is entitled to vote (according to age, civil rights, census, etc.) or may establish compulsory turnout (Belgium, Greece, Australia, etc.).

However, in order for the elections to be free, no citizen should be forced to have a certain choice or attitude towards elections. As such, the case where voting is compulsory is somewhat controversial.

The electoral system is the mechanism regulating the electoral process itself (the way to vote, the counting of the votes) and awarding the victory in the elections. Electoral systems are grouped, mainly, in majority and proportional representation, according to the rules of the district and national levels. There are indeed other types of electoral systems, but these are combinations and subtypes of these systems.

The institutionalisation of elections and electoral systems aims, besides a party system suitable for democracy, at the rallying of citizens to the democratic regime through their active participation in the political game. This attachment can be observed by the electoral turnout, an important dimension of the quality of democracy. Pippa Norris shows a greater popular participation in proportional systems, because, being a system that is fairer for voting citizens, they are more willing to participate in it. The data shows that the electoral participation in plurality systems is on the average around 65.4%, while proportional systems turn around 75.7 %.[22]

The electoral system influences the party system. The electoral system maximizes or reduces the variety of institutionalised political views. Thus, a proportional model allows a large number of parties to speak in parliament, while the majority system will most likely produce a two-party system, the small and medium parties being quickly side-lined. Some types of party systems that are theoretically possible actually become apparent: there is no three-party system, there are no heavily unbalanced systems.[23]

The Duverger Law (1955) shows that the plurality vote favours the emergence of a two-party system, while proportional vote generates multipartidism: “simple majority electoral system with a single ballot favours the emergence of a two-party system”.[24] Although Duverger does not say it from the start that the electoral system itself causes the emergence of the two-party system, and its adoption will result in a short time (1-2 general election), in the elimination of virtually all except two of the parties on that political arena. Consequently, there is a reverse causal correlation: “a simple majority system, with two ballots, and proportional representation favours multipartism”.[25]

The proportional representation increases the number of parties and consequently the options available for the voters. Furthermore, proportional representation makes elections more competitive, so parties are strongly motivated to try to maximize support in all districts.

The only advantage of majority voting and the two-party system is that it reduces the probability of ideological polarization. Electoral provisions exclude from the party system radical political actors, and the need to win votes of the centre encourages moderation. Thus, minimizing the extremist parties and the centripetal forces of the electoral messages that stimulate competition between parties favours the stability of democracy.

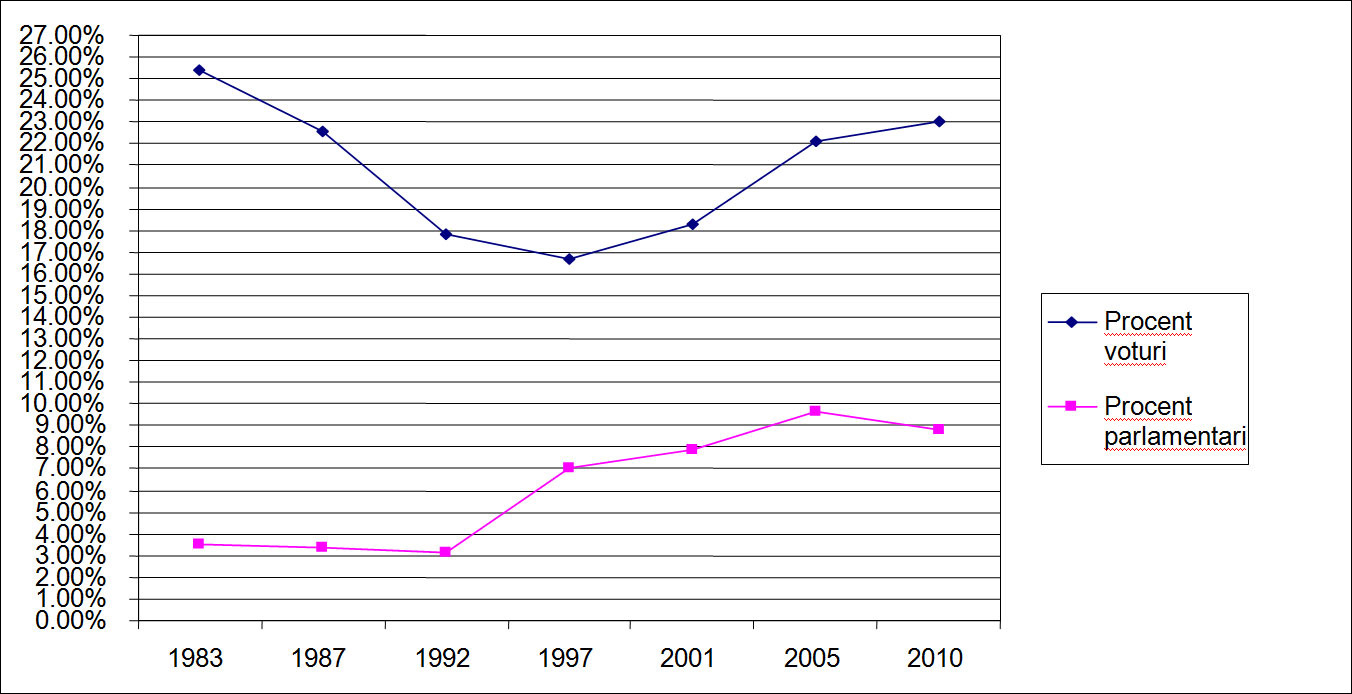

The distorting effect of majority voting is very noticeable in the British system, where the Liberal Democratic Party’s national voting percentage is consistently quite close to that of the first two parties, but is strongly penalized in the composition of parliament.

Fig. 1: Evolution of voting and representation Liberal Democrat, UK

Source: BBC - Election 2010 (www.bbc.co.uk/election/), page consulted on 10.05.2011.

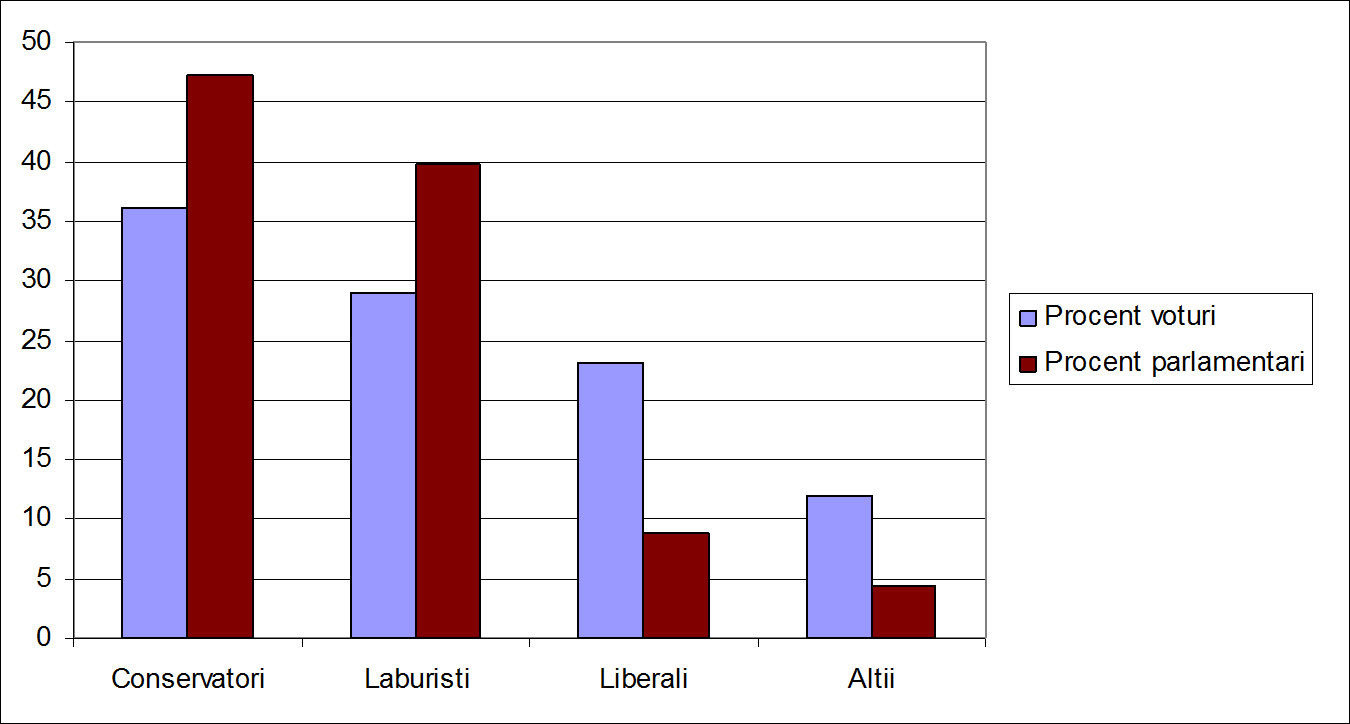

In the general election of 2010, the percentage of citizens represented by the Liberal Democrats was far lower than the percentage of their voters. The plurality voting system effectively eliminates a significant percentage of votes, by simply redistributing them to other parties. In this case, it appears that 15-20% of the citizens were represented in parliament by politicians against whose parties they voted.

Fig. 2: Voting and parliamentary representation in the 2010 elections, United Kingdom

Source: BBC - Election 2010 (www.bbc.co.uk/election/), page consulted on 10.05.2011.

The election system determines the party system. Thus, a proportional system provides representation to all political forces that have passed a certain threshold, while the majority system will inevitably lead to the survival of only two relevant parties in parliament, and elimination of the others, below an estimated threshold of 20-25% of the popular vote. Mathematically speaking, through this system, a party with 20%, even 25% votes nationally, although an obviously high percentage, is likely to win fewer constituencies, which would disproportionately reduce its number of MPs. At the same time, parties with 30-35% of votes will win the election, virtually eliminating the vote of as much as one fifth of the electoral turnout.

The majority voting system is based on single-member constituencies, while the proportional system is based on voting lists. There is no superior democratic value for the single-member compared to the list system. It would be the same as saying that U.S. senators are elected more democratically than their German, French or Spanish counterparts. In reality, the option as to the vote system has little to do with improving the democratic quality of a regime, but entirely to do with the fact that voting in single-seat districts is the mark of the plurality voting system, which, in turn, will generate a two-party system. With the establishment of a pure single ballot vote – thus a plurality vote system – the result will be the quick elimination of small and medium-sized parties from parliament and the increase of the seats for the largest ones.

Going back to the theoretical argumentation, the relationship between the electoral system and the party system works the other way around as well. For instance, Josep Colomer considers[26] that the number of parties determines the choice of a particular type of electoral system, before it had the chance to produce its effects on the party system. Large parties would prefer small parliaments, small constituencies and restrictive seat allocation system (eg. simple plurality, high electoral threshold). On the other hand, where there are several small parties, they would prefer a large parliament, with large electoral districts and proportional seat allocation, in order to increase the chances to be included in the parliament. Therefore, as Daniel Barbu highlights, during the transition, “East European political parties preferred multi-partisan system created by proportional representation and subsequent coalition risk.” [27]

Also, the political actors, naturally pursuing their own interest, will choose to establish electoral rules that reduce the probability of becoming absolute losers. This situation exists in plurality voting systems (parliamentary or presidential), on the “winner-takes-all” principle. Plurality voting involves periodic risk exclusion from the government. Proportional systems have more than one winner (usually because such systems rarely produce a party with over 50% of the seats), and the probability that the current loser might accede to power – even before the next election – is acceptable.

The two-party system has advantages such as: the majority party will form the government alone, giving it stability (and therefore effectiveness), but also drawbacks, such as the lack of interest in any other political opinion, even of those who did manage to entry the parliament. From this point of view, a proportional system provides more fairness for all parties and a more accurate representation of all interests expressed politically in the society.

If there are more than two parties in a system, it will be difficult for a single one of them to secure a parliamentary majority, so the many parties in parliament will use the solution of forming coalition, which – although looks like it could cause government instability – actually produces compromises that mitigate the radicalism of the “winner-takes-all” position.

In a plurality system, the actors’ incentive to accept and participate is reduced, because their odds of defeat are very high (50%). In a proportional system, there can be more winners (those who will form the ruling coalition) and a larger chance of victory. The fact that there are many actors who can form a government, regardless of the votes obtained, reduces significantly the chances of total electoral defeat, which proportionally increases the interest of all political actors to participate in politics and to accept the democratic political game. Normally, each political actor wants a bigger chance to participate, in any way, to an electoral victory, and they find such odds in the proportional system. Political actors who champion plurality systems are interested in benefiting alone, therefore completely, from the levers of executive power.

The winner-takes-all mentality is much less democratic, because it gives total victory to one of the actors, despite a margin of electoral support that could very well be quite limited. Hence the superior democratic quality of the parliamentary democracy over the presidential one, and of the proportional system over the plurality.

In conclusion, the plurality system in single winner districts reduces the quality of democratic representation, and, coupled with the presidential system which favours the concentration of power in the hands of just one person, increases the risk of failure of democratic transition and consolidation.

Bibliography

BARBU, Daniel, “De la partidul unic la partitocraţie” în Jean Michel DE WAELE, Partide politice şi democraţie în Europa Centrala şi de Est, Humanitas, București, 2003.

BLONDEL, Jean, “Types of Party System”, in Peter MAIR (ed.), The West European Party System, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1990.

CHEIBUB, José Antonio, Fernando LIMONGI, “Democratic Institutions and Regime Survival: Parliamentary and Presidential”, Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 5, 2002.

CHEIBUB, José Antonio, Adam PRZEWORSKI, Sebastian SAIEGH, “Government Coalitions and Legislative Success under Presidentialism and Parliamentarism”, British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 34, 2004, pp. 565-587.

COLOMER, Josep, “It’s Parties That Choose Electoral Systems (Or Duverger’s Laws Upside Down)”, UPF Economics and Business Working Paper 812, March 2005.

DIAMOND, Larry, Marc PLATTNER, The Global Resurgence of Democracy, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1993.

DUVERGER, Maurice, Political Parties: Their Organization and Activity in the Modern State, Wiley Science Ed., New York, 1963.

FISH, Steven, Matthew KROENIG, The Handbook of National Legislatures. A Global Survey, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009.

HUNTINGTON, Samuel, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century, University of Oklahoma Press, Oklahoma, 1991.

LIJPHART, Arend, Modele ale democraţiei. Forme de guvernare şi funcţionare în treizeci şi șase de țări, Polirom, Iași, 2000.

LINZ, Juan, “The Perils of Presidentialism”, Journal of Democracy, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1990.

LINZ, Juan, STEPAN, Alfred, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1996.

MAINWARING, Scott, Timothy SCULLY (eds.), Building Democratic Institutions: Party Systems in Latin America, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 2000.

MAINWARING, Scott, Matthew SHUGART, “Juan Linz, Presidentialism, and Democracy: A Critical Appraisal”, Comparative Politics, Vol. 29, No. 4 (July 1997), pp. 449-471.

NORRIS, Pippa, “Choosing Electoral Systems: Proportional, Majoritarian and Mixed Systems”, International Political Science Review/ Revue internationale de science politique, Vol. 18, No. 3, July 1997.

RIKER, William, Liberalism against Populism, W. H. Freeman, San Francisco, 1982.

STEPAN, Alfred, Cindy SKACH, “Constitutional Frameworks and Democratic Consolidation: Parliamentarism Versus Presidentialism”, World Politics, Vol. 46, 1993.

VALENZUELA, Arturo, “Latin American Presidencies Interrupted”. Journal of Democracy, Vol 15, Nr 4, Oct. 2004, pp. 5-19.

[1] Larry DIAMOND, Marc PLATTNER, The Global Resurgence Of Democracy, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1993, p. 97.

[2] As we will later see, this condition is best fulfilled in parliamentary democracy, with proportional electoral system.

[3] For the comparative details of all democratic structures, see Steven FISH, Matthew KROENIG, The Handbook of National Legislatures. A Global Survey, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009.

[4] Ibidem, p. 131.

[5] Juan LINZ, “The Perils of Presidentialism”, Journal of Democracy, Vol. I, No. 1, Winter 1990, p. 63.

[6] Alfred STEPAN, Cindy SKACH, “Constitutional Frameworks and Democratic Consolidation: Parliamentarism Versus Presidentialism”, World Politics, Vol. 46, 1993; Arturo VALENZUELA, “Latin American Presidencies Interrupted”, Journal of Democracy, Vol. XV, No. 4, Oct. 2004, pp. 5-19; Juan LINZ, “The Perils of Presidentialism”, Journal of Democracy, Vol. I, No. 1, 1990, pp. 51-69.

[7] Scott MAINWARING, Timothy SCULLY (eds.), Building Democratic Institutions: Party Systems in Latin America, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 2000, p. 33.

[8] Scott MAINWARING, Matthew SHUGART, “Juan Linz, Presidentialism, and Democracy: A Critical Appraisal”, Comparative Politics, Vol. 29, No. 4 (July 1997), pp. 449-471.

[9] Jose Antonio CHEIBUB, Adam PRZEWORSKI, Sebastian SAIEGH, “Government Coalitions and Legislative Success under Presidentialism and Parliamentarism”, British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 34, No. 4, 2004, pp. 565-587.

[10] Scott MAINWARING, Matthew SHUGART, “Juan Linz, Presidentialism…cit.”, p. 23.

[11] Juan LINZ, “The Perils of Presidentialism…cit.”, p. 56.

[12] Jose Antonio CHEIBUB, Adam PRZEWORSKI, Sebastian SAIEGH, “Government Coalitions…cit.”, p. 577.

[13] Ibidem, p. 580.

[14] Ibidem, p. 579.

[15] William RIKER, Liberalism against Populism, W. H. Freeman, San Francisco, 1982, p. 14.

[16] Arend LIJPHART, Modele ale democraţiei. Forme de guvernare şi funcţionare in treizeci şi șase de țări, Polirom, Iași, 2000, p. 38.

[17] Alfred STEPAN, Cindy SKACH, “Constitutional Frameworks...cit.”, p. 18.

[18] José Antonio CHEIBUB, Fernando LIMONGI, “Democratic Institutions and Regime Survival: Parliamentary and Presidential”, Annual Review of Political Science , Vol. 5, 2002, p. 151.

[19] Ibidem, pp. 151-152.

[20] Juan LINZ, Alfred STEPAN, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1996, p. 93.

[21] Samuel HUNTINGTON, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century, University of Oklahoma Press, Oklahoma, 1991, pp. 266-267.

[22] Pippa NORRIS, “Choosing Electoral Systems: Proportional, Majoritarian and Mixed Systems”, International Political Science Review/ Revue internationale de science politique , Vol. 18, No. 3, Jul. 1997, pp. 297-312.

[23] Jean BLONDEL, “Types of Party System”, in Peter MAIR (ed.) The West European Party System, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1990, p. 310.

[24] Maurice DUVERGER, Political Parties: Their Organisation and Activity in the Modern State, Wiley Science Ed., New York, 1963, p. 217.

[25] Ibidem, p. 239.

[26] Josep COLOMER, “It’s Parties That Choose Electoral Systems (Or Duverger’s Laws Upside Down)”, UPF Economics and Business Working Paper 812, March 2005.

[27] Daniel BARBU, “De la partidul unic la partitocraţie” in Jean Michel DE WAELE (ed.), Partide politice şi democraţie in Europa Centrala şi de Est, Humanitas, 2003, p. 263